In 2019, all Nobel prizes in science were awarded to men.

After the biochemical engineer Frances Arnold won the Nobel in chemistry in 2018 and Donna Strickland in physics in 2018, the old order was restored.

Strickland was the third woman physicist to receive the Nobel Prize, following Marie Curie in 1903 and Maria Goeppert-Mayer 60 years later. When asked how she felt, she said it was surprising at first to realize that the number of women who won the award was small:

“I live in a male dominated world, so it’s not surprising to see male domination in this field as well.”

The low number of women Nobel laureates raises questions about their exclusion in education and the profession. Women researchers have come a long way over the past century. Unfortunately, there is overwhelming evidence that women are underrepresented in science, technology, engineering and mathematics.

Studies have shown that while continuing their academic careers, women face obstacles, either explicitly or indirectly. Women, who are approached with prejudices, are seen by men as foreigners or symbolic workers.

However, when women achieve success in sports, politics, medicine and science, they are seen as role models by little girls and other women.

Traditional stereotypes argue that women “do not like math” or “are not good at science”.

Both men and women voice these thoughts, but researchers have managed to disprove their ideas. Research shows that women stay away from the fields of science, technology, education and medicine not because of cognitive inadequacy, but because of educational policy, cultural context, stereotypes and lack of role models.

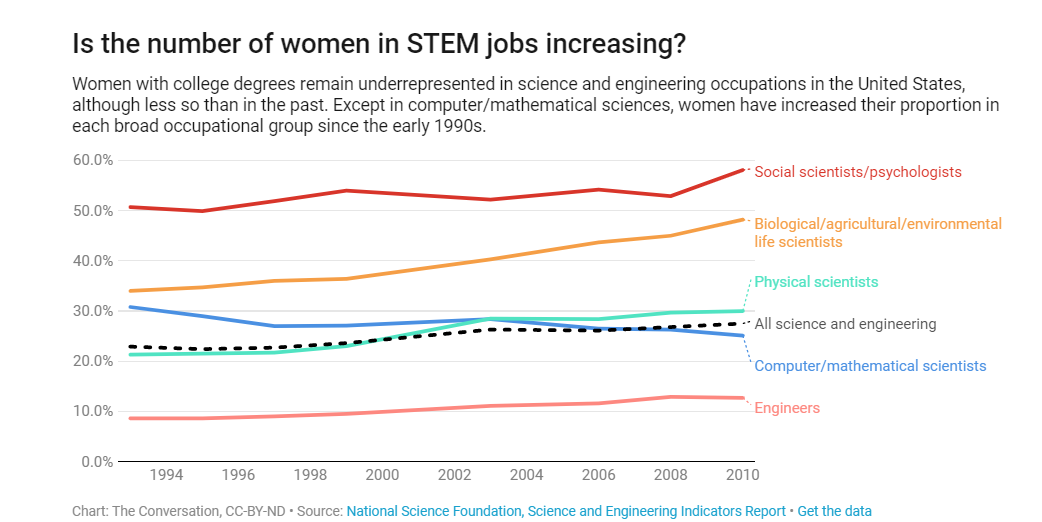

However, this approach is changing. Women make up more than half of those working in psychology and social sciences. Computer and mathematical sciences are becoming more and more present in the scientific workforce, with the exceptions.

According to the American Institute of Physics, since 1975 women have increased their bachelor’s degrees by 20% and their doctorate in physics by 18%.

Women continue to encounter glass cliffs and ceilings as they progress through their academic careers, even if they land in good positions with a PhD.

What challenges do women face?

The nature of academic science makes it difficult for women to stand out in the workplace and balance work-life responsibilities. Bench science (such as a chemist) may require working long hours in a laboratory. Tenure makes it difficult if not impossible to maintain work-life balance, respond to family obligations, and have children.

Additionally, working in male-dominated workplaces can make women feel isolated. Often excluded from networking opportunities and social events, they may feel outside of the laboratory culture, academic department, and field.

When women do not have a critical mass in a workplace – that is, when they do not make up 15% of employees – they have a hard time defending themselves. They are more likely to be perceived as a minority or an exception.

Women who have few female colleagues are less likely to engage with collaborators or networks of support and advice. This isolation can be exacerbated when women are unable to attend work events or attend conferences because they deal with family and childcare responsibilities.

Universities and professional organizations are working to correct many of these barriers.

Efforts include creating family-friendly policies, increasing transparency in salary reporting, providing mentoring and support programs for female scientists, preserving research time for female scientists and hiring women, and providing research support. But these programs have had mixed results.

For example, it is thought that family-friendly policies such as childcare in the workplace can further increase gender inequality, which in turn may reduce research productivity for men.

Implicit prejudices about scientists

We all—the public, the media, university staff, students, professors—have an idea of what a scientist or a Nobel Prize winner looks like. This idea is predominantly male and brings to mind an elderly person.

This is an example of implicit bias; one of the unconscious, involuntary, natural and inevitable assumptions we all make about the world. People make decisions based on subconscious assumptions, preferences, and stereotypes—even if sometimes it’s against what they openly believe.

Studies show that prejudice against women is widespread. The fact that the rate of granting research scholarships to men is higher than that to women also supports this research.

Implicit biases hinder women’s recruitment, advancement and recognition of their work. For example, academic job seekers are more likely to rate based on their personal information and physical appearance. Letters of recommendation for women tend to arouse suspicion and may result in the use of language that has negative career outcomes.

Women’s research is less likely to be cited by others, and their ideas are more likely to be attributed to men. At the same time, women’s personal authorship searches take twice as long because of their review process.

The respect shown to female scientists for their achievements is often less than they deserve. Research shows that people tend to use their last name when talking about male scientists, and use their first name when talking about female scientists.

So why is this important? That’s because studies show that individuals with surnames are more likely to be seen as famous and distinguished. In fact, one study found that calling scientists by their last name made people think they deserved 14% more awards.

We hope that one day all this discrimination will come to an end. We see days when men and women are equal individuals, and people are not left behind because of a feature they cannot choose, such as their gender!