Although it is hard to believe, it is news from the modern world, people living in complete isolation continue to exist today. People living in isolation from this world appear in many places, from the untouched parts of the Amazon jungle to the dense and forested mountains of Asia. Who are the people living in isolation from the whole world in this content? Together, we know these primitive tribes closely.

Himbalar

The Himba are an indigenous people with an estimated population of about 50,000 living in northern Namibia, in the Kunene District (formerly Kaokoland) and around the Kunene River in the south.

A few groups remained from the OvaTwa, also called the OvaHimba, but were hunter-gatherers. However, OvaHimba do not like to be associated with OvaTwa. Culturally distinct from the Herero people, the OvaHimba are a semi-nomadic, pastoralist people, within which they speak the OtjiHimba language, a variant of the Herero belonging to the Bantu family. The OvaHimba are semi-nomadic as they have basic farms where crops are planted, but may have to move throughout the year depending on where there is rainfall and access to water. The OvaHimba are considered the last (semi) nomadic people of Namibia.

Women and girls tend to perform more labor-intensive tasks than men and boys, such as carrying water to the village, plastering mopane wood houses with a traditional mixture of red clay soil and cow dung binder, collecting firewood, taking care of the housework. Within the community, there are artisans who produce sour milk and work to safely supply it, making handicrafts, clothing and jewelry with the gourd vines used for cooking and serving. The responsibility of milking the cows and goats also belongs to women and girls.

Women and girls look after the children. A woman or girl also takes care of another woman’s children. The main duties of the men are to take care of the livestock, graze animals in places where they are usually away from their families for long periods of time, slaughter animals, build construction and establish councils with village chiefs.

Andamanese Tribe

The Andamans are various indigenous peoples of the Andaman Islands, part of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands union territory of India in the southeastern part of the Bay of Bengal in Southeast Asia.

Andamanese peoples are among the groups considered Negrito because of their dark skin and small stature. The Andamanites lead a hunter-gatherer lifestyle as per their tradition.

For thousands of years they have lived in considerable isolation. It is suggested that the Andamanians settled in the Andaman Islands about 26,000 years ago at the last glacial maximum. Among the Andaman peoples were the Great Andaman and Jarawa of the Great Andaman archipelago, the Jangil of Rutland Island, the Onge of Lesser Andaman, and the Sentinelese of North Sentinel Island.

At the end of the 18th century, when they first came into constant contact with foreigners, there were an estimated 7,000 Andaman in the area. Over the next century, they experienced a massive population decline, due to epidemics of foreign diseases and loss of land. Today, with the extinction of the Jangil, only roughly 400-450 Andamans remain. Only the Jarawa and the Sentinelese maintain resolute independence, refusing to make contact with outsiders.

Jarawalar

The Jarawas are the indigenous people of the Andaman Islands of India. They inhabit parts of the South Andaman and Central Andaman Islands. Their current number is estimated to be between 250-400 individuals.

They largely avoid interaction with strangers. Many aspects of their societies, cultures and traditions are poorly understood. Along with other indigenous Andaman peoples, they have lived on the islands for several thousand years. The Andaman Islands have been known to foreigners since ancient times; but until fairly recently they were rarely visited.

Such contacts were predominantly sporadic and temporary. For most of their history, their only significant contact has been with other Andamanite groups.

For many years, contact with the tribe declined quite significantly. There are some indications that the Jarawa, despite outnumbering (and eventually surviving) Jangil, viewed the now-extinct Cengil tribe as a parent tribe from which they split centuries or millennia ago. The Jangil (also known as Rutland Island Aka Bea) was assumed to be extinct in 1931.

Awa Tribe

The Awá are the indigenous people of Brazil who live in the Amazon rainforest. It has about 350 members and 100 of them have no contact with the outside world. They are considered extremely endangered due to conflicts with logging interests in their own territory.

The Awá people speak Guajá, a Tupi-Guaraní language. Those who originally lived in the settlements adopted a nomadic lifestyle around 1800 to escape European invasions.

In the 19th century, the Awá came under increasing attack by European settlers in the area, who cleared most of the forests from their land. Beginning in the 1800s, the Awá people adopted an increasingly nomadic lifestyle to avoid European settlers.

Since the mid-1980s, some Awálar have been relocated to modern settlements by the government. For the most part, however, they were able to lead their traditional way of life in nomadic groups of a few dozen people, completely far from their forests, with little or no contact with the outside world.

In 1982, the Brazilian government obtained a US$900 million loan from the World Bank and the European Union. One condition of this loan was the isolation and protection of the lands of certain indigenous peoples, particularly the Awá. This was of particular importance to the Awá, with the forest on which they stood and the many tribal people whose forests were increasingly invaded by foreigners and killed by settlers.

Had it not been for this government intervention, the ancient culture of the Awá people would have been in danger of extinction. However, the Brazilian government has been extraordinarily slow to deliver on its commitment. After 20 years of continuous pressure from campaign organizations such as Survival International and the previously Forest Peoples Program, Awá’s lands were finally drawn in March 2003. Meanwhile, encroachment and a series of massacres reduced their numbers to around 300, of whom only 60 still lead the traditional hunter-gatherer lifestyle.

Pirahã Tribe

The Pirahã are the indigenous people of the Amazon Rainforest in Brazil. They are the only surviving subgroup of the Mura people and are hunter-gatherers. They mainly inhabit the banks of the Maici River in Humaitá and Manicoré in the state of Amazonas.

As of 2018, their number is 800 individuals. The Pirahã people do not call themselves Pirahã, but rather Hi’aiti’ihi, which roughly translates as “flat ones”.

they call someone else language “crooked head”. Pirahã members can whistle in their own language; this is how Pirahã men communicate while hunting in the jungle.

As far as Pirahã relates to researchers, their culture is concerned only with subjects that fall directly into personal experience. Therefore, there is no history beyond living memory. Some words in Pirahã:

Baíxi (parent, grandparent or elder),

Xahaigi (sister, male or female),

Hoagí or hoísai (son), kai (daughter), and piihí (stepchild, favorite child, stepchild, at least one deceased parent, and more).

Also, the language they use is called the Pirahã language.

El Molo Tribe

The El Molo, also known as the Elmolo, Dehes, Fura-Pawa, and Ldes, are an ethnic group mainly living in the north Eastern Province of Kenya. Historically they spoke the El Molo language as the mother tongue, the Afro-Asian language of the Cushitic branch, and now most of them speak El Molo Sambur.

It is estimated that El Molo originally migrated from Ethiopia in the more northerly Horn region to the Turkana Basin around 1000 BC. It is thought that due to the arid lands they migrated to, they later left their agricultural activities for lake fishing.

Historically, El Molo has built burial structures where they place their dead. A 1962 archaeological survey in the Northern Frontier Region led by S. Brodribb Pughe observed hieroglyphics in some of these structures.

El Molo has historically spoken the El Molo language as a mother tongue. It is a language belonging to the Cushitic branch of the Afro-Asian family. Most group members have now adopted the Nilo-Saharan languages of their neighbours.

Māoris

Māoris are quite famous among the people who live in isolation from the world. Māori are the indigenous Polynesian people of mainland New Zealand (Aotearoa). The Māori were made up of settlers from Eastern Polynesia who arrived in New Zealand in several waves of waka (canoe) expeditions between about 1320 and 1350.

Over several centuries in isolation, these settlers developed their own distinctive culture, whose language, mythology, craft, and performing arts developed independently of other Eastern Polynesian cultures. Some early Māori moved to the Chatham Islands, where their descendants are the Moriori, New Zealand’s other indigenous Polynesian ethnic group.

Beginning in the 18th century, initial contact between Maori and Europeans ranged from beneficial trade to deadly violence. Māori actively adopted many technologies from those who came at that time

With the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840, the two cultures coexisted for a generation. Increasing tensions over disputed land sales led to conflicts and major land confiscations in the 1860s, to which the Māori responded with fierce resistance.

The treaty was declared legally void in 1877. After being adopted, Māori forced them to assimilate into many aspects of Western society and culture. Social turmoil and epidemics of introduced diseases have had devastating consequences on the dramatically falling Māori population.

By the early 20th century, the Maori population had begun to rebound, and by focusing on the Treaty of Waitangi, they increased their position in wider New Zealand society. They have made efforts to achieve social justice.

Hulls

The Huli are an indigenous people living in the Hela Province of Papua New Guinea. Huli and Tok Pisin talked. Many also speak some of the surrounding languages. Some have also learned English. It is one of the largest cultural groups in Papua New Guinea and has more than 250,000 people (2011).

He describes in different ways what the Huli have lived in their region for thousands of years. There is information that they tell long oral histories about individuals and their clans. They lived as nomads (mainly for trade) in the highlands and plains surrounding their homeland, especially in the south.

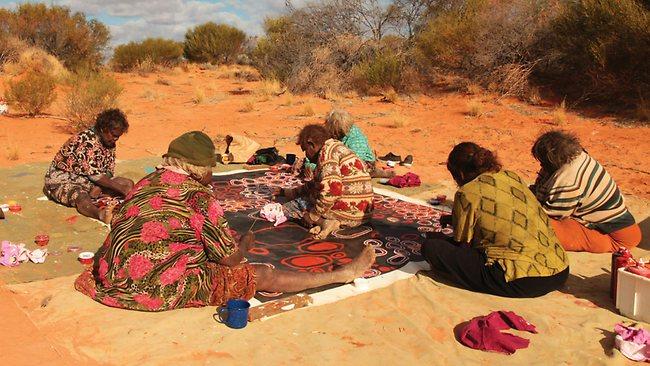

Pila Nguru

The Pila Nguru, often referred to in English as the Spinifex people, are an Aboriginal Australian people of Western Australia whose territory extends to the South Australian border and north of the Nullarbor Plain.

Their homeland is located in the Great Victoria Desert in Tjuntjunjarra, about 700 kilometers east of Kalgoorlie. The Pila Nguru are the last people of Australia to continue their traditional way of life.

In Australia, they largely maintain their traditional hunter-gatherer lifestyle within the region, where their claim to indigenous title and related collective rights was recognized by a Federal Court decision of 28 November 2000. An art project was launched in 1997, in which Native paintings were part of the title request. A major exhibition in London in 2005 attracted great interest from artists.

marshes

The Batak is one of about 140 indigenous peoples of the Philippines. The Batak is one of the indigenous peoples of Palawan. Since ancient times, they have inhabited a 50-kilometer series of river valleys along the northeastern coastline that is today Puerto Princesa City.

It showcases the short builds, dark skin, and curly hair that have earned them their name for people who look physically predatory. Its economic activities are mostly in the form of farming, hunting and collecting natural resource products. Primarily, resin extraction is based on collecting honey.

Their food comes only from forest rivers, streams and sometimes the sea. They are extremely active people. This is the main reason why they are not motivated to create permanent land areas for crop production. Traditionally they only plant cassava, bananas, sweet potatoes, ube, gabi and coconut.

The religious belief of the Bataks continues to be based on the spirits of nature. The Holy Spirits, whom they believe to live on big rocks and trees, have the power to cure serious diseases when called by their bees.

The population of Batak at the turn of the century is estimated at 1,000. However, the last census in 1990 left them with only 450 people. The modern world is really not a phenomenon that can be easily used by people living in isolation from the rest of the world.